Integrated Food and Energy project a sentinel in Northern Australia development

In the previous edition of Business Acumen, we presented a brief overview of the Etheridge Integrated Agriculture Project (EIAP). This innovative agribusiness and power generation development is a sentinel for what is possible in Northern Australia by integrating agribusiness savvy, sustainability, new technologies and vital infrastructure to realise the potential of the region. In this edition, we present a more detailed report on the EIAP – and the intelligent drive behind it.

By Mike Sullivan >>

THE Etheridge Integrated Agriculture Project (EIAP) can potentially lead the way for a range of future sustainable agribusiness developments across Northern Australia – because it astutely plays to the strengths of the region and overcomes the significant challenges.

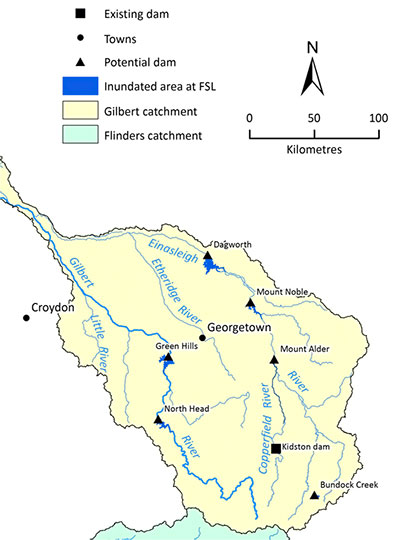

First, it makes the most of abundant water, using the Einasleigh and Etheridge River systems to integrate deep lake water storage with cattle pastures, sugar, guar bean and stock feed production, electricity generation from bagasse, and aquaculture.

The project is steeped in the experience – and passion for North Queensland – of three well-known business leaders. Stewart Peters is a chemical engineer and manufacturing and resources specialist; John Grabbe is a water harvesting specialist who was joint managing director of Australia’s largest private irrigator Cubbie Group Ltd; David Hassum is an infrastructure finance specialist and InterFinancial director; and Keith De Lacy is a former Queensland Treasurer and chairman of Macarthur Coal .

Their company, Integrated Food and Energy Developments (IFED), is raising funds to commence work in 2017.

EIAP is founded on 65,000 hectares of irrigated cropping in the Etheridge Shire, in Queensland’s southern Gulf country, with cattle on a further 200,000ha and aquaculture incorporated. It develops a series of gravity flow deep water lakes which store water away from the river system itself. In total, there will be 18,000ha devoted to deep water storage, minimising evaporation.

“There is a fairly natural water storage area quite close, so it’s just gravity diversion,” Mr De Lacy said. “The first storage is 1.6 million megalitres, which is about the size of (Brisbane Valley’s) Wivenhoe and has an average depth of 14 metres which makes it highly efficient. We will gravity feed it down to a smaller one in the cropping area which has got 400,000 megalitres. So that is about 2 million megalitres we would store.”

Research by IFED on 100-plus years of records show that, had the lake system been in place, it would not have gone dry at any stage, supporting full production despite extensive drought periods. Mr De Lacy said about 90 million megalitres of water flows into the Gulf each year – that is about three times the volume of the Murray-Darling river system – and the Gilbert River system is 5.5 million megalitres of that flow.

“We are looking for an allocation of 550,000 megalitres per annum, which is 10 percent of the flow,” Mr De Lacy said. “There is a rule of thumb in Australia – two-thirds for the environment, one third for harvesting. We are only looking for 10 percent, so that leaves plenty for the environment and for other users.”

An innovative approach is off-river storage, not dams on rivers.

“We call it partial flow diversion, which means we take some of the flood flows and it is much more ecologically sustainable,” Mr De Lacy said. “The first flows go down the river and we only take a percentage of the big flows.

“All of those rivers are heavily monsoonal, they flood in the monsoon season and are then dry for most of the year.

“On 100 years of river flow data, we would have got a full crop every year. So it is 100 percent sustainable. That’s because we are storing about four times what we need.”

The products of the EIAP are also an innovative mix of sugar, guar gum (from the guar bean legume), meat and electricity from the sugar bagasse.

The project generates its own power and exports electricity to the grid.

There is also a supply of sugar for possible ethanol production.

Mr De Lacy said guar is used as a food thickener and also has a special use in the shale fracking process.

“That sort of underwrites its price and volume,” he said.

The EIAP will also produce about 400,000 tonnes of stock feed a year.

“Which then means we can run a meat processing plant because we can feed the stock in the off-season,” Mr De Lacy said. “There is a million cattle in that region, but they all lose weight in the off season, so they stop going to abattoirs, and because abattoirs only work eight months of the year they are never viable. With our stock food we can get 12 months supply.

“We produce all of our own electricity and some – it’s all bagasse, it’s all coking. We justify the capital spend on the co-gen (power co-generation) by what we can sell into the grid. The rest of it we use ourselves – it is effectively free to us.”

WASTE-NOT WANT-NOT

Another EIAP innovation is the utilisation of lake-fed ponds for the production of redclaw, a crayfish native to the region.

“But we also found that the wastewater from our processing plants, the sugar mill and the abattoir and so forth, we feed in to an anaerobic digester, which creates methane, which is energy, but what is left in the water is a sort of a carbohydrate enzyme which is food for redclaw,” Mr De Lacy said.

“So we effectively feed them for free. We are only using the water one more time and, when they are finished with the water, we use it for irrigation and they actually add nutrient to the water which helps the irrigation as well.

“We did a quick exercise on that and we would produce 7500 tonnes of redclaw, which is worth $100 million. And that is just an add-on. As is the abattoir.”

Mr De Lacy said even though the region has been used for beef cattle for more than 100 years, meat processing was not originally a focus of the project.

“We did not start off with beef, but because we have got the electricity and the stock feed, it’s another add-on,” he said.

Because of the backgrounds of the IFED founders, the plan to integrate processes, as they flowed from having a sound water supply, drove the decisions on the eventual production mix.

“The reason our project works so well is its scale to start off with,” Mr De Lacy said. “You have got to be big enough to do your own processing, in those isolated regions.

“Our project is a billion dollars of production each year and 1000 employees.”

CAPITAL RAISING

IFED has secured agreements with the four required properties in the region and is concurrently conducting both environmental impact studies and fund raising.

“The environmental assessment process is the main part, to ensure sustainability,” Mr De Lacy said.

“We are confident, as we are only proposing to use only 10 percent of the river flow. We will be subject to the most rigorous environmental assessment program that any project has ever been subjected to. But we are confident about it. We have done a lot of work and a lot of science on it.”

Mr De Lacy said Cubbie Station in Western Queensland was where off-river water storage was successfully pioneered in Australia – and John Grabbe was the driving force behind that development. Now his experience and the unique advantages of applying that system North Queensland, were setting a new paradigm in agricultural development.

Ironically, the sustainable agribusiness approach by IFED should also help in the regeneration of native plant and wildlife in the region.

“All this savannah country in Cape York Peninsula is very lightly timbered, it has had cattle running over it for more than 100 years,” Mr De Lacy said. “It is infested with plant and animal feral species – rubber vine and wild pigs and all sorts of things.

“So it is not pristine country, not at all. Dogs are not as bad there as they are further south, but they are there too. Pigs are the worst. We would have to have a regime that is controlling them, which would help everybody a bit, too.

“And it (the project) is 100 percent carbon sustainable.”

Mr De Lacy said while the capacity was there to produce and utilise ethanol, it was so far undecided.

“I am reluctant to get involved in a crop that depends on a government subsidy,” he said. “And they keep changing the excise regime.

“We have done an exercise that produces 100 megalitres of ethanol. Plus we have all of our own electricity and we sell electricity into the grid – so that’s all renewable. We could produce 100 megalitres of ethanol on our numbers, that is nine times the amount of liquid fuel that we would consume. Excess would go into the refinery market – E10.

“We have just got to decide whether we proceed with that. Otherwise it all just goes into sugar. So it is really just an economic decision.”

VALUE IN SCALE

As a showcase for what might be achieved in terms of sustainable development in Northern Australia, the project has attracted initial support from both the Federal Government and the Queensland Government.

“In round terms, the value of our production is around $1 billion (a year), and our profit each year is around $350 million, so there’s $600 million in consumables – labour, consumables, services, what-have-you – in Northern Australia,” Mr De Lacy said. “So everybody benefits.

“The Commonwealth Government has always been strongly supportive. And it is consistent with their white paper. The State Government is supporting it now,” he said, pointing out that a memorandum of understanding on satisfying environmental requirements, before the water allocations would be made, had to be re-negotiated when the new Labor Government came to office in January 2015, setting the project on hold for several months.

“We have now got a memorandum of understanding with the Queensland Government that effectively guarantees the same thing.”

Mr De Lacy said the major advantage needed for successful agriculture in Northern Australia is “scale”.

“You can produce so much biomass in the tropics – you have got masses of water, sunshine, soil – which is really stored energy,” he said. “That overcomes a major economic disadvantage of being out there, when you have got all of your own electricity.”

He said it was also to the project’s advantage to utilise – and help to improve and extend – local existing infrastructure.

“We would have an accommodation village, a bit like some of the resource projects have, but we would hope that a town like Georgetown would grow to accommodate a permanent workforce,” he said.

“It is the Etheridge Shire capital. And it was a much bigger town 100 years ago than it is now. That was all mining country – gold and copper and so forth. They had their days, Croydon, Georgetown, and Kidston of course.”

The challenges EIAP faces are different to, say, establishing a mining operation in the region – and more long-term.

“Big mining projects are a more well-trodden path,” Mr De Lacy said, from his experience as chairman of Macarthur Coal. “This is new. What we say is that if we can provide this pathway, there are quite a number of others in Northern Australia. And that includes the Northern Territory.

“Just putting dams here, there and everywhere, you don’t get real economic development out of that,” Mr De Lacy said. “Governments should be measuring the value of production and jobs created per megalitre, to allocate water. We have got a rule of thumb that we can produce $2000 worth of production per megalitre – and we absolutely will exceed that over time – but that is what governments should look at.

“So, (at the moment) some water gets allocated … everybody wants a bit of water, but what do they do with it? Irrigate a pasture? There is not much real economic activity coming out of it.”

Where the major challenge rests right now is in getting financial supporters to agree to the vision – and recognise the financial upside presented in the projections. IFED believes most of its support will come from the private sector.

“I wouldn’t think governments, unless we access the Northern Australia Infrastructure Fund, which is concessional loans,” Mr De Lacy said. “No, we would be looking to raise our money in the private market. The returns are there. We have got an IRR – internal rate of return – of 16-20 percent. Which makes it fundable.

“We would be 18 months from bankable to get to construction. It would be three years before you were in full production after that.”

INFRASTRUCTURE BACKBONE

While the EIAP is self-sustainable and profitable from a very early stage, the main challenge and advantage in such a development in the southern gulf is in developing the infrastructure than leads to it. This is where governments come in to play.

“It is a $2 billion project,” Mr De Lacy said. “There is a road right to the Port of Townsville. We have to use the Port of Townsville – you couldn’t go through Cairns because the road system and the port system is not good enough. In a few places (the road) needs some work. But we do not need a lot of further infrastructure. The beauty of scale, again – the small infrastructure we do it ourselves.

“There is a small railway line that goes through Georgetown to Cairns, but it needs that much work on it now. It’s a very old system. It is just kept there for heritage reasons now.

“We would probably put a light plane strip there. We may even look at more as time goes on. With beef, maybe, or redclaw (to move it by air) you never know, it depends on where it is going.”

What Mr De Lacy and the IFED team hope is that their Northern Australia project will be a catalyst for other intelligent sustainable developments that will help the region realise its true potential.

“There is a mature beef industry (in the region) that generates a lot of revenue, but does not generate a lot of jobs,” Mr De Lacy said.

“In the coastal regions there are viable communities – Darwin, Cairns, Townsville – and they are growing viable communities. But if you are going to transform the large part of Northern Australia, I believe that we have unlocked the mechanism, as it were, or found the model.

“We have looked at all of these major projects that have been tried over the years and worked out why they did not work, including the Ord. You know, it has been quite problematical over the years.”

Failed or underwhelming projects IFED looked at included Lakeland Downs at Cooktown, Tipperary Land Corporations and Territory Rice Ltd in Darwin, Northern Agricultural Development Corporation in Katherine and the Ord River Project in Kununurra.

Mr De Lacy said the old ways of developing the North were ripe for failure.

“The old system was government did the water infrastructure, then they had farmers, a whole range of farmers, usually supervised by government, resuming land and cutting it up. And then you had separate processing,” Mr De Lacy said.

“So you really just did not have that integration that we believe is necessary. For example, in the Ord, the price of sugar went down and the farmers started growing something else. So how does the mill carry on? Whereas what we are talking about is one owner of the water, the farming and all the infrastructure.

“There are two lots of integration – water, farming and infrastructure – and then within the infrastructure what I said before: the waste of one becoming the feed stock of the other. And you can do that if you own it all.

“I grew up in the sugar industry where the farmers and millers have been fighting each other for 100 years … it’s madness.”

TECHNOLOGY ADVANTAGE

Perhaps the biggest catalyst for success, Mr De Lacy believes, is that IFED can integrate the latest, most economical technologies from day one.

“That’s another advantage we have in starting from scratch with those things, instead of bolting them on,” he said. “Important to us is that everything we are doing has been done … except that we will do the latest and greatest of it.

“For instance, in beef processing they have almost got it automated to that extent that it’s incredibly efficient. While we will be looking to employ a lot more people than what’s employed now, we would be looking to automate and utilise robotics and the modern technologies.”

In that respect, Mr De Lacy said the versatility of the operation meant the EIAP had looked at diversification in advance. For example, a dairy operation using the right technologies would also be possible and profitable because of the scale.

“We had a look at a diary option, which works,” he said. EIAP modelled 89,000 milking cows in evaporative air-conditioned barns, using the latest milking robotics of what is known as the ‘California system’.

“They have got one in Saudi Arabia with 67,000 head or something,” Mr De Lacy said. “It delivers 800 million litres of fresh milk a year. The air conditioning is really just a really fine water spray and a fan … The cattle just live in there, you do not have to shut the door. They can walk out if they like – but they don’t. Why would they go out into 35 degrees when it is 23 inside and all the food’s in there?”

But that option is on the backburner while the foundation product mix of EIAP proves itself.

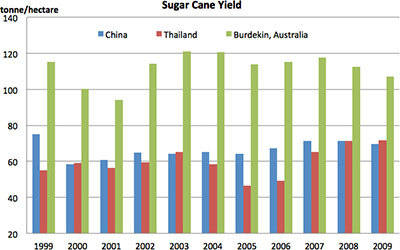

The most secure of these is sugar.

“We picked sugar … Indonesia is the fastest-growing sugar market in the world at the moment,” Mr De Lacy said. “And they are very close. It is one of those middle class crops that are going to continue to grow. But the three things about it are the biomass, we know how to do it in Queensland, and it is a mature market – there are forward markets and so forth for sugar cane. You can manage the price of it a lot better than some other crops.

“And you would always export the power (from the co-generation plant).” Currently the area’s power is drawn from Rockhampton, with all the liabilities and losses of that long distance power transmission.

EIAP could also become a sentinel for successful beef production in Northern Australia. Mr De Lacy said the current big problem for the industry was its cyclical nature – cattle lose significant weight in the dry season so the industry struggles to supply abattoirs and live trade at certain times of the year.

“Why would you send it in for processing today when it was 10kg heavier a month ago? You would have sent it in then. To balance it out you need stockfeed somehow.”

The stockfeed is EIAP’s advantage, and it offers flexibility.

“We may not even run the cattle, we may just do a feedlot arrangement for the last bit – or we may just do a deal with them (regional cattle farmers) and give it to them, so long as we get it back as it goes through the abattoir,” Mr De Lacy said.

“From the livestock point of view, in the region and in those three or four shires, there would be animal welfare benefits in the sense that stock would not be losing their weight and they would be processed on site instead of going 1000km in the back of a truck or something.”

He said animal welfare benefits over what exists today were a clear positive.

“We look at all those issues, environmental/sustainability issues we’ve looked hard at them and we believe we have got them covered,” Mr De Lacy said.

“With trickle tapering irrigation, which we would use, you have got the precision application of nutrient and water. So you don’t have the problem of run-off which has been the issue on the east coast over the years for the Great Barrier Reef.

“We have got the big advantage that we are not (flowing) in to the Great Barrier Reef, I‘ve got to say that. But nevertheless we won’t have nutrient run-off at all. Why would you have it running off if you can organise it properly, which we can?"

PLUGGING IN AGBOTS

Mr De Lacy said the EIAP was planning to take advantage of the latest technologies from day one – including keeping an eye on agricultural robot systems being developed in Queensland by QUT and Swarm Farm.

“(Agricultural robots) that go along and zap a feral plant with insecticide, or microwave or whatever, and just get the one that is growing, that’s all. We would be looking at those,” Mr De Lacy said.

“And drones … they are using those now in the cattle industry. They fly around the fence and just photograph if the fence is good … but we would have other uses for those too. And all automation as well.

“Starting from scratch, you’ve got a great opportunity. I keep saying to our mob, you have got one chance to make this really efficient. It’s the first one.

“I reckon we will grow sugar cheaper than anywhere in the world, simply because of technology and our production systems. I think our production will be just extraordinary. We have the sunshine and the water.”

He believes the systems in place for sugar production at the EIAP will out-perform the Burdekin area.

“We believe we have taken the weather out of the equation, which is pretty rare in agriculture,” Mr De Lacy said. “We have drought proofed it, and we are 300km from the coast, where the cyclones are too. A rain depression is all it is when it gets there. I’ve grown up on the coast with those cyclones and they can have a major impact.”

And he is delighted at the opportunities EIAP hopes to provide for regional Indigenous people.

“It is a great opportunity for Indigenous people,” Mr De Lacy said. “And we have committed, actually, to 10 percent of the workforce being Indigenous.”

He said the IFED team hoped the project could create far more Indigenous opportunities.

“We would like a lot of our people to be contractors. Individual contractors to own the tucks and run their own businesses – one would hope you could get Indigenous involvement in that,” Mr De Lacy said.

“It’s a big challenge, it’s not easy. We have an Indigenous fellow with us based in Cairns and he will access Federal money for training and work ready programs. The secret is, if you get enough there, it will work.”

At age 75 and making many of his presentations to prospective investors on his latest iPad, Keith De Lacy nominates the Northern Australia development as “the most exciting project I’ve been involved with”.

That’s quite a statement coming from the former chairman of Macarthur Coal, Queensland Sugar Ltd and Cubbie Group, who remains on the national board of the Australian Institute of Company Directors and who was Queensland Treasurer and Minister for Regional Development from 1989-1996.

“The only problem is getting people to believe in it.”

ends

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?