CEDA: Will 5 million Australian jobs be superseded?

MORE than five million jobs – that is almost 40 percent of Australian jobs that exist today – are in the firing line from the digital revolution, research by the Committee for the Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) has found.

A new CEDA report shows a ‘moderate-to-high’ likelihood of those jobs available today disappearing in the next 10 to 15 years, due to technological advancements. While there are new jobs being created by the same digital economy forces, questions remain over the future of work in Australia.

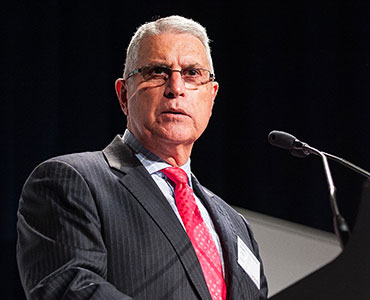

CEDA chief executive Stephen Martin said Australia and the world is on the cusp of a new but very different industrial revolution “and it is important that we are planning now to ensure our economy does not get left behind”.

Professor Martin said, in releasing CEDA’s major research report for 2015, Australia’s Future Workforce? that changes were especially going to impact Australia’s regional economies.

Prof. Martin said as part of the report, the National ICT Australia (NICTA) group researchers had examined the probability of job losses due to computerisation and automation in Australia and in each local government area across the country.

“This research shows that in some parts of rural and regional Australia in particular there is a high likelihood of job losses being over 60 percent,” Prof. Martin said.

Prof. Martin said there will be new jobs and industries that emerge, but if Australia is not planning and investing in the right areas “we will get left behind”.

“The pace of technological advancement in the last 20 years has been unprecedented and that pace is likely to continue for the next 20 years,” he said.

“While we have seen automation replace some jobs in areas such as agriculture, mining and manufacturing, other areas where we are likely to see change are, for example, the health sector, which to date has remained largely untouched by technological change,” Prof. Martin said.

“Creating a culture of innovation must be driven by the private sector, educational institutions and government. However, government must lead the way with clear and detailed education, innovation and technology policies that are funded adequately.

“Our labour market will be fundamentally reshaped by the scope and breadth of technological change, and if we do not embrace massive economic reform and focus on incentivising innovation, we will simply be left behind in an increasingly competitive global marketplace.

“Currently the commitment needed to link education and innovation policy with funding is appalling compared to other countries and Australia’s industry innovation strategy is woefully underfunded compared to global competitors,” Prof. Martin said.

“For example the five Industry Growth Centres announced last year by the Federal Government should be critical in driving innovation but only $190 million has been allocated over four years.

“In comparison, the UK Catapult Centres, which they are based on, have been allocated almost $3 billion over the same period.

“The German Fraunhofer Network, the Netherlands’ Top Sectors Strategy and US National Manufacturing Institutes have had even larger allocations.

“If we expect to compete with countries such as these as a smart and innovative economy then we need to get serious about how we invest in driving innovation.”

Prof. Martin said Australia also needed to reconsider how it would deal with reskilling workers as particular fields of employment disappear.

“The CEDA report highlights the policy approach taken by Denmark to reskill mature age workers,” he said.

“The Danish approach is three pronged – greater flexibility around hiring and firing, generous unemployment benefits and substantial programs to help unemployed people gain new skills. Often these programs start before a person is even retrenched.

“In comparison Australia has the lowest levels of unemployment benefits of the OECD for a single person recently unemployed and often programs to assist with skills training do not start until a person has been unemployed for some time.

“The Danish model is underpinned by the same mutual obligation approach to Australia but rather than send people off on work-for-the-dole projects, it is training people with the skills their economy needs,” Prof. Martin said.

“The Danish policy, while more expensive initially, makes long-term economic sense because it ensures people return to the workforce more quickly and with the skills the economy needs.

“As more job restructuring occurs in the Australian economy this type of policy is going to be vital.

“It is likely some tough decisions about the Australian labour market will need to be made in the next decade; we’ve already had a taste of this with the decline of the car manufacturing industry.

“However, if we develop the right policies now, we have the potential to reduce the impact of these challenges and ensure our economy remains robust.”

The Australia’s Future Workforce? report will be launched at the Sofitel Melbourne at noon on June 16.

The Australia’s Future Workforce? report’s contributing authors include Telstra chief scientist and technology officer, Hugh Bradlow, Deakin University vice-chancellor Jane den Hollander, and IBISWorld founder and chairman, Phil Ruthven.

The launch event will be followed by a series of events being held in Adelaide, Gold Coast, Brisbane, Sydney and Perth.

The CEDA research report Australia’s Future Workforce?can be downloaded from the CEDA website here.

ends

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?